IV

31

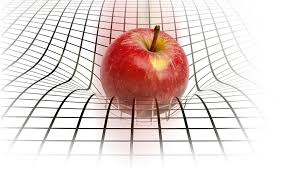

Dinner at the Inn would have been very good if any of the four had been paying attention to the food. They were all a bit overwhelmed by what they had decided Ken had accomplished, or at least tried. But there were other distractions as well. They sat at a square table, men one side, women on the other. Min and Rafael, sitting opposite each other, kept finding their feet meeting. Blushing. Nora, sitting across from the boy she had hoped might be her son-in-law, kept thinking what a nice place The Apple Tree would be for a wedding reception. Now that boy--man--was obviously thinking worrisome thoughts. As the desert cart was being brought to their table, he shared his thoughts.

‘It’s like Heisenberg, and I think it would make returning from a time journey very difficult.’

Nora did not like the sound of that. Her clearest memory of Heisenberg was that it had to be compensated for in Star Trek. ‘What does that mean?”

‘The problem is that “here” is not just moving through time, it is also moving through space. If the four of us could travel, say, three hundred years into the past, and stay for even a very short time and return, three hundred years into what would then be our future, this ‘here’ would have moved somewhere else. ‘Here’ relative to the ‘here’ we left might be just a few inches down the table, or it might be in the parking lot, or in Hereford, or somewhere off the earth.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Nora, who was beginning to think that she really would never see her son again.

‘It’s not that different from a railroad schedule, really. We bought tickets from London to Castle Cary, a distance of 170 kilometers. The schedule said that we would arrive in two hours and five minutes. But that arrival time was really just a probability. There are many variables that could affect the actual arrival time. We arrived a few minutes early Thursday. So, if we had bought a ticket, not for a destination in space but a destination in time, we would have had to leave the train between here and Taunton. Or, if there had been some major slowdown outside of London, we might only have gotten so far as Reading in two hours and five minutes. And railroads have the advantage of tracks, which at least gives us an idea of where we might get let off. There don’t seem to be tracks in time travel.

‘What I’m saying is that the universe is very complex, and the calculations necessary to predict where or when someone traveling on Kenneth’s time waves are beyond the capabilities even of today’s quantum computers.’

‘So, it’s hopeless? Nora looked horrified.

‘No. Not hopeless. Just that I think it’s probably useless for us to wait around Ken’s garage for him and Atilla to return. They could easily return, if they do, in Brighton or in a suburb of New Delhi. Maybe in the English Channel--which wouldn’t be too bad’, he added when he saw the horrified look on Nora Owens’ face, ‘because Atilla the Hyundai would certainly float, and we know it has great radios.’

‘I have an idea that might help.’ It was Rafael who spoke, who had been considering what Marcus was saying very carefully. ‘Everything you say is true. And there are even more complications, because waves interact with each other in all sorts of ways, bouncing and augmenting and cancelling. But we know quite a lot about wave travel, starting with mankind’s early ocean voyages. We have long known that there are recurring local patterns of waves, patterns we can use to travel. My ancestors traveled from Spain to the Americas using such knowledge. Kenneth Owens’ idea for detecting weak but time waves reminded me of a book I read long ago, a book I had forgotten until this evening. It was written by another Kenneth, whose last name I don’t remember right now, but it tells how Polynesian sailors find their way across vast expanses of the Pacific to tiny islands by feeling the waves and currents through the hulls of their dugout canoes. The patterns remain stable for centuries, and they are recorded in songs that are taught to young sailors. The book is called ‘A Song for Satawal’. So, Kenneth got his inspiration from the songs of his ancestors, the songs his grandmother taught him. Maybe part of what those songs contain is information about time travel. I have been doing a little reading about some of the celtic legends. Tell me what you know about leylines.’

16

Owain signaled for his men to gather closely. The town looked grand, indeed, but what town it might be, they had no idea. They were not expecting it. But they had expected nothing that had happened to them since they had wakened. It was decided that Ieuan Wyn would enter the town and find out what he could about where they were and what dangers they might expect. Kenneth moved a ways down the hill and crouched in some bushes to try to get a better look at the town, as well. He didn’t quite recognize it, but it didn’t look so strange to him as it did to the others. And, of course, Aidan Prydudd listened for anything he might put into his story, but he stayed as close as he could to Kenneth.

It was not long before Ieuan returned, in a panic. ‘The town is Pengenffordd. Everything is crazy. I could hardly understand the people, and they thought I was crazy. They say Wales was defeated long ago. And they say that a woman, Anne, is queen.’

‘How can we be in Powys?’ Every man had this or similar questions, none of them answerable by Ieuan, who was usually level headed, nor by Owain, who was usually in command of any situation. ‘Bewitched.’ There had been stories that the English had sent a sorcerer after Owain. That might explain the storm, and the mist, and their sleeping. That might explain the stranger. He was the sorcerer. ‘Where was he hiding?’

Aiden found Kenneth first, and told him that he must leave immediately. Owain thought he was a sorcerer. Ieuan thought the town was Pengenffordd, so they must be bewitched. And, Aiden insisted, he wanted to go with Kenneth, especially if he were a sorcerer.

No comments:

Post a Comment