Wednesday, October 31, 2018

17. Monuments for time travelers

33

The detectives went back to Ken’s little cottage, Home, and looked again at his notes about celtic disappearances and descriptions of ‘thin places’. They looked at the maps of ley lines that had been composed over the years, maps that had usually been considered pseudo-scientific rubbish. But most scientists had thought that the atomic theory was rubbish between the time of Democritus and John Dalton, and it was not until J. J. Thompson that they really began to be taken seriously. There were a lot of correspondences with places Ken had studied and the ley lines. One particularly ‘strong’ line was supposed to run northwest from Glastonbury towards Aberliefenni in Wales, where a band of Welsh warriors were supposed to be ‘sleeping’ in a slate mine. It seemed likely that this might be a good location for Kenneth’s route. If that were his route, however, tracking him would not be easy. There wasn’t any schedule of time travel departures on the net, and they didn’t expect to see any tracks.

Min thought that there might be tracks. If he had left from Glastonbury Tor on some sort of wave, there might have been, might still be, remnants of his wake. She thought her nano antennae might be able to detect it. It was not clear how they would know what it was, however,even if they saw.

So it was decided that the next part of their project would be to construct a wake detector. It would be a lot like the array printed on Kenneth’s Atilla, but it could probably be simpler. There was certainly no need for it to be attached to a vehicle. Marcus envisioned it as a sort of shield-shaped panel, light and stiff and looking like something that might have been carried at Camelot. He could work on it at Sheffield. Rafael would propose to his team at Panjiva that they would benefit from closer work with the Royce Institute at Sheffield. Min-seo probably needed to play her cards a little closer, since Kenstel expected that they would put her ideas into production somehow. So, it would be their last night in Pilton, at least for a while. Marcus went with Nora to the cottage, Home, and they looked at some of the photos on the Table before Marcus returned to the Apple Tree. Min-seo and Rafael opened the door between their rooms.

In the morning the Apple Tree’s Volvo deposited them at Platform 3 for the 07:27 train to Paddington. Rafael and Min-seo were a little disappointed that Marcus and Nora joined them in First Class for this trip, but they had decided the upgrade was worth it for breakfast, since it was such an early departure. Before the day was over, they would all be back at their own homes, with that strange feeling one sometimes has after a trip that one has never left at all.

34

‘You can come with me,’ Ken told Aiden, ‘but only if you trust me. I am no wizard, but the full story of how I came to be here will be hard for you to believe. But first I need to get into the town and see if what Ieuan said is true. Owain and his men probably won’t look for me there for a while, and if it is true, I can get us out of here without them finding us, I think.’

‘I trust you’.

It was as Kenneth had expected. Owain had looked for him to go back the way they had come. They quickly decided that the wizard had taken the young bard as some sort of hostage, so they spread out along the rock and steep way they had come, moving slowly and finding nothing.

‘I think I can find all the information I need at a church. We must try not to be noticed. If we are, let me speak. I will, if you don’t mind, say you are my servant.’

No one paid them much attention. It was a Sunday. There were not many people about doing business, and no one seemed to think it strange that they were heading towards church. What Owen was looking for wa indeed found on the wall of the porch of the church, where notices were placed. Much to Aidan’s surprise, St. John’s Priory was now the Brecon Parish Church. The announcements were in English, which Aidan couldn’t read, but they did tell Owen that it was indeed the year of our Lord 1704, the second year of the reign of Anne, Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland, There was, to Aidan’s delight, no mention of Wales. Was Wales independent once more?

‘We need to hide now,’ said Owen. I can get us back to where we met, but we need to travel at night. I have been here before, hiking as a boy.’

‘There’s not much moon. How can we see?’

Don’t worry. I have a light.’

And so Owen and Aiden headed into a bit of forest on a hill above the town until dark, when Owen showed Aiden a bit of the magic of the slab of glass he carried in his pocket.

Eventually, Owain and his company returned to the town, where they were generally thought to be mad. There were stories of a band of heroes led by an Owain Lawgoch who were supposed to be sleeping in a slate quarry further up the Dragon’s Back. who would awake to become King of the Britons. Now this madman claimed he was Owain. But the men were allowed to work, since they had no families to take them in, and gradually even they began to accept that their earlier lives had been a dream. Owain and Ieuan, however, continued to insist on their story, and spent the last years of their lives in prison for fighting. Ieuan was lucky he wasn’t hanged, because he had come close to killing a man who called him a lunatic.

Tuesday, October 30, 2018

16. Space time is hard for time travellers.

IV

31

Dinner at the Inn would have been very good if any of the four had been paying attention to the food. They were all a bit overwhelmed by what they had decided Ken had accomplished, or at least tried. But there were other distractions as well. They sat at a square table, men one side, women on the other. Min and Rafael, sitting opposite each other, kept finding their feet meeting. Blushing. Nora, sitting across from the boy she had hoped might be her son-in-law, kept thinking what a nice place The Apple Tree would be for a wedding reception. Now that boy--man--was obviously thinking worrisome thoughts. As the desert cart was being brought to their table, he shared his thoughts.

‘It’s like Heisenberg, and I think it would make returning from a time journey very difficult.’

Nora did not like the sound of that. Her clearest memory of Heisenberg was that it had to be compensated for in Star Trek. ‘What does that mean?”

‘The problem is that “here” is not just moving through time, it is also moving through space. If the four of us could travel, say, three hundred years into the past, and stay for even a very short time and return, three hundred years into what would then be our future, this ‘here’ would have moved somewhere else. ‘Here’ relative to the ‘here’ we left might be just a few inches down the table, or it might be in the parking lot, or in Hereford, or somewhere off the earth.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Nora, who was beginning to think that she really would never see her son again.

‘It’s not that different from a railroad schedule, really. We bought tickets from London to Castle Cary, a distance of 170 kilometers. The schedule said that we would arrive in two hours and five minutes. But that arrival time was really just a probability. There are many variables that could affect the actual arrival time. We arrived a few minutes early Thursday. So, if we had bought a ticket, not for a destination in space but a destination in time, we would have had to leave the train between here and Taunton. Or, if there had been some major slowdown outside of London, we might only have gotten so far as Reading in two hours and five minutes. And railroads have the advantage of tracks, which at least gives us an idea of where we might get let off. There don’t seem to be tracks in time travel.

‘What I’m saying is that the universe is very complex, and the calculations necessary to predict where or when someone traveling on Kenneth’s time waves are beyond the capabilities even of today’s quantum computers.’

‘So, it’s hopeless? Nora looked horrified.

‘No. Not hopeless. Just that I think it’s probably useless for us to wait around Ken’s garage for him and Atilla to return. They could easily return, if they do, in Brighton or in a suburb of New Delhi. Maybe in the English Channel--which wouldn’t be too bad’, he added when he saw the horrified look on Nora Owens’ face, ‘because Atilla the Hyundai would certainly float, and we know it has great radios.’

‘I have an idea that might help.’ It was Rafael who spoke, who had been considering what Marcus was saying very carefully. ‘Everything you say is true. And there are even more complications, because waves interact with each other in all sorts of ways, bouncing and augmenting and cancelling. But we know quite a lot about wave travel, starting with mankind’s early ocean voyages. We have long known that there are recurring local patterns of waves, patterns we can use to travel. My ancestors traveled from Spain to the Americas using such knowledge. Kenneth Owens’ idea for detecting weak but time waves reminded me of a book I read long ago, a book I had forgotten until this evening. It was written by another Kenneth, whose last name I don’t remember right now, but it tells how Polynesian sailors find their way across vast expanses of the Pacific to tiny islands by feeling the waves and currents through the hulls of their dugout canoes. The patterns remain stable for centuries, and they are recorded in songs that are taught to young sailors. The book is called ‘A Song for Satawal’. So, Kenneth got his inspiration from the songs of his ancestors, the songs his grandmother taught him. Maybe part of what those songs contain is information about time travel. I have been doing a little reading about some of the celtic legends. Tell me what you know about leylines.’

16

Owain signaled for his men to gather closely. The town looked grand, indeed, but what town it might be, they had no idea. They were not expecting it. But they had expected nothing that had happened to them since they had wakened. It was decided that Ieuan Wyn would enter the town and find out what he could about where they were and what dangers they might expect. Kenneth moved a ways down the hill and crouched in some bushes to try to get a better look at the town, as well. He didn’t quite recognize it, but it didn’t look so strange to him as it did to the others. And, of course, Aidan Prydudd listened for anything he might put into his story, but he stayed as close as he could to Kenneth.

It was not long before Ieuan returned, in a panic. ‘The town is Pengenffordd. Everything is crazy. I could hardly understand the people, and they thought I was crazy. They say Wales was defeated long ago. And they say that a woman, Anne, is queen.’

‘How can we be in Powys?’ Every man had this or similar questions, none of them answerable by Ieuan, who was usually level headed, nor by Owain, who was usually in command of any situation. ‘Bewitched.’ There had been stories that the English had sent a sorcerer after Owain. That might explain the storm, and the mist, and their sleeping. That might explain the stranger. He was the sorcerer. ‘Where was he hiding?’

Aiden found Kenneth first, and told him that he must leave immediately. Owain thought he was a sorcerer. Ieuan thought the town was Pengenffordd, so they must be bewitched. And, Aiden insisted, he wanted to go with Kenneth, especially if he were a sorcerer.

31

Dinner at the Inn would have been very good if any of the four had been paying attention to the food. They were all a bit overwhelmed by what they had decided Ken had accomplished, or at least tried. But there were other distractions as well. They sat at a square table, men one side, women on the other. Min and Rafael, sitting opposite each other, kept finding their feet meeting. Blushing. Nora, sitting across from the boy she had hoped might be her son-in-law, kept thinking what a nice place The Apple Tree would be for a wedding reception. Now that boy--man--was obviously thinking worrisome thoughts. As the desert cart was being brought to their table, he shared his thoughts.

‘It’s like Heisenberg, and I think it would make returning from a time journey very difficult.’

Nora did not like the sound of that. Her clearest memory of Heisenberg was that it had to be compensated for in Star Trek. ‘What does that mean?”

‘The problem is that “here” is not just moving through time, it is also moving through space. If the four of us could travel, say, three hundred years into the past, and stay for even a very short time and return, three hundred years into what would then be our future, this ‘here’ would have moved somewhere else. ‘Here’ relative to the ‘here’ we left might be just a few inches down the table, or it might be in the parking lot, or in Hereford, or somewhere off the earth.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Nora, who was beginning to think that she really would never see her son again.

‘It’s not that different from a railroad schedule, really. We bought tickets from London to Castle Cary, a distance of 170 kilometers. The schedule said that we would arrive in two hours and five minutes. But that arrival time was really just a probability. There are many variables that could affect the actual arrival time. We arrived a few minutes early Thursday. So, if we had bought a ticket, not for a destination in space but a destination in time, we would have had to leave the train between here and Taunton. Or, if there had been some major slowdown outside of London, we might only have gotten so far as Reading in two hours and five minutes. And railroads have the advantage of tracks, which at least gives us an idea of where we might get let off. There don’t seem to be tracks in time travel.

‘What I’m saying is that the universe is very complex, and the calculations necessary to predict where or when someone traveling on Kenneth’s time waves are beyond the capabilities even of today’s quantum computers.’

‘So, it’s hopeless? Nora looked horrified.

‘No. Not hopeless. Just that I think it’s probably useless for us to wait around Ken’s garage for him and Atilla to return. They could easily return, if they do, in Brighton or in a suburb of New Delhi. Maybe in the English Channel--which wouldn’t be too bad’, he added when he saw the horrified look on Nora Owens’ face, ‘because Atilla the Hyundai would certainly float, and we know it has great radios.’

‘I have an idea that might help.’ It was Rafael who spoke, who had been considering what Marcus was saying very carefully. ‘Everything you say is true. And there are even more complications, because waves interact with each other in all sorts of ways, bouncing and augmenting and cancelling. But we know quite a lot about wave travel, starting with mankind’s early ocean voyages. We have long known that there are recurring local patterns of waves, patterns we can use to travel. My ancestors traveled from Spain to the Americas using such knowledge. Kenneth Owens’ idea for detecting weak but time waves reminded me of a book I read long ago, a book I had forgotten until this evening. It was written by another Kenneth, whose last name I don’t remember right now, but it tells how Polynesian sailors find their way across vast expanses of the Pacific to tiny islands by feeling the waves and currents through the hulls of their dugout canoes. The patterns remain stable for centuries, and they are recorded in songs that are taught to young sailors. The book is called ‘A Song for Satawal’. So, Kenneth got his inspiration from the songs of his ancestors, the songs his grandmother taught him. Maybe part of what those songs contain is information about time travel. I have been doing a little reading about some of the celtic legends. Tell me what you know about leylines.’

16

Owain signaled for his men to gather closely. The town looked grand, indeed, but what town it might be, they had no idea. They were not expecting it. But they had expected nothing that had happened to them since they had wakened. It was decided that Ieuan Wyn would enter the town and find out what he could about where they were and what dangers they might expect. Kenneth moved a ways down the hill and crouched in some bushes to try to get a better look at the town, as well. He didn’t quite recognize it, but it didn’t look so strange to him as it did to the others. And, of course, Aidan Prydudd listened for anything he might put into his story, but he stayed as close as he could to Kenneth.

It was not long before Ieuan returned, in a panic. ‘The town is Pengenffordd. Everything is crazy. I could hardly understand the people, and they thought I was crazy. They say Wales was defeated long ago. And they say that a woman, Anne, is queen.’

‘How can we be in Powys?’ Every man had this or similar questions, none of them answerable by Ieuan, who was usually level headed, nor by Owain, who was usually in command of any situation. ‘Bewitched.’ There had been stories that the English had sent a sorcerer after Owain. That might explain the storm, and the mist, and their sleeping. That might explain the stranger. He was the sorcerer. ‘Where was he hiding?’

Aiden found Kenneth first, and told him that he must leave immediately. Owain thought he was a sorcerer. Ieuan thought the town was Pengenffordd, so they must be bewitched. And, Aiden insisted, he wanted to go with Kenneth, especially if he were a sorcerer.

Monday, October 29, 2018

15. Apple trees can have guests.

29

Yanto Owens may not have been worried about his son, but he was proud of him. It had taken him a while to recognize that Kenneth’s stubbornness was a gift from himself, and even longer to appreciate it. So, although he did not think that time travel had been Ken’s project, he was pretty sure that whatever it was, he would almost certainly complete it successfully.

While Nora was at the Paddington Starbucks, Yanto was in his shop, playing with simulations of potential valence interactions of heavy metals. Some might call his shop a man cave, but Yanto always called it the shop. England was a nation of shopkeepers, not of cavemen. Like many such shops, it was full of parts of past projects and tools, old and new. Yanto, for instance, still had an antique 4K TV that he used as a monitor for most of his work. But it was connected to a new Chromebox about the size of an antique Altoids box. With it he could use virtually any sort of computer software he needed, probably running on hardware housed along some Norwegian fjord or a frozen Russian lake.

It had not taken people very long to realize what first they considered waste or litter was actually simply resources that were unavailable to them. Local entropy. But it took hardly more time for people to develop the tools to use that waste, just as bacteria had quickly developed that fed on the plastic in the oceans. Yanto was working on recovery of heavy metals that were scattered about as ‘waste’ in all sorts of places, from folks’ livers to last year’s computer. As he reviewed the properties of Thallium, he noticed some of the past projects gathering dust on the shelf behind his screen. One was Kenneth’s first 3-D printer. He had bought it as soon as the price of printers dropped to less than 1000 pounds. He had used to make models of Star Trek ships to sell to support his more serious projects. Another was a metal box that at first might seem to be a blue biscuit tin.

The blue box was a pc that Kenneth had built twenty years ago. He had left it behind when he went up to university, replacing it with a normal laptop. Yanto had used it for a while, but he too had bought a replacement as computing power got cheaper and cheaper, so it went up on the shelf. Ken had wanted it to be as small as possible to house an Nvidia GTX 580. He had built his own motherboard for the brand new Core i7, and Yanto had helped him make the case, which was the heatsink. The case got a little warm, but it kept the insides cool enough to avoid thermal throttling. Kenneth would joke that it was cooler on the inside. It looked like a Tardis.

Yanto smiled. Perhaps his son had gone time traveling. Kenneth might be a real Time Lord.

30

The four detectives met early on Friday morning around Kenneth’s table. House provided everyone breakfast, and decided it needed to order more groceries if it were going to be having guests. Surprised to find had been on the same train the evening before, they were met at the station by The Apple Tree’s Volvo Estate, and enjoyed high tea at the Inn and outlined what they thought they might do to solve the mystery. Then Nora had taken an Uberdu to her son’s cottage and the others had gone to their rooms. Both Lin and Rafael had wanted to stay up with each other, but they both feigned jet lag and retired to their rooms, separated by a locked door. Marcus retired to his room with his Yogabook to review once again the schematics of all the little circuits he had printed on the surface of Kenneth’s Hyundai. None of them had slept well.

So they had gathered early at Kenneth’s cottage for breakfast and to pursue their outline. The trio who had stayed at the inn skipped its famous breakfast for breakfast prepared by the House. House made each one’s choice, and decided it should order more groceries if it were to be having guests. Breakfast plates cleared away, they woke the Table to implement their plan.

First, they wanted to compare all the records of what Kenneth had done to the Hyundai with to the information Min-seo had provided him. What had he done that might be beyond what Marcus had printed or known. They wanted to know what sort of vehicle it was in which Kenneth was traveling.

Then, they wanted to study all of Kenneth’s notes about his concepts of time travel, especially his interest in tales of ‘sleepers’--usually knights or monks who woke after years of being asleep, often in some cave. Was he planning on going forwards or backwards. Did he have a specific time and place as his destination? If he had tried to go to a specific place in the past, they might find evidence of his success in historical records. Or not. They wanted to know what sort of route had he planned to take.

Next, they wanted to compare and analyze all of the data to see if they might understand better just how Kenneth had done the deed. Because, after all, he had done something. He had just disappeared. It was not easy to disappear in 2030, with everything and everyone connected. None of Nora’s or Marc’s social networks had told them that their friend Kenneth Owens was near, or had checked in, or had posted, or had commented. Because he had left his Table open, they could see that he had not withdrawn any funds just before Halloween, nor were there any unusual withdrawals in the weeks before. He had not planned on taking holiday funds with him, and he had left his bankcard behind. It was obvious that Kenneth had thought he was going time-traveling. Had he? Was that possible? And if Kenneth were not somewhen else, where else was he?

Because of the reviews of their correspondence and notes done before, it was quickly obvious that nothing had been done with the actual antennae on the Hyundai beyond what Min-seo had theorized. Marcus had managed to build it, and Rafael was wondering whether, after the weekend were over, if he could get Rutchsman to work for Panjiva. Certainly his company needed to strengthen their ties to Sheffield. Kenneth’s breakthrough, if he had really made it and was not just craftily hiding out, either dead or alive, somewhere in a crevice of Snowdonia, had been in software. He had further developed some nearly-forgotten work on optical analysis at the University of California and the work done by the LSST to find a way to identify what the thought of as time waves in ‘real time’--an odd concept when one thinks of it. He had relied on his Nvidia Plank One to show his waves graphically. He had taken his graphics card with him (those things are expensive, and he had wanted to be able to use it whenever he landed. He would be able to understand when he was even if he couldn’t get back to when when he had left.) But Marcus was able to use an Nvidia cloud service to see how it might work. Kenneth was traveling, if that was what he was doing, in a cross between an extremely-broad band spectroscope and a surfboard. Rafael laughed. He had been a fan of Norrin Rad as a kid.

The route Kenneth had expected to take was quickly obvious, and no surprise. He had taken seriously the stories of thin places and sleepers and crossing between worlds that were so common in Celtic tales. It seemed that Glastonbury might be a sort of station, a node, for the roads that led to other times and worlds, a sort of stone and iron age Paddington Station. Following that metaphor, however, they had no way of knowing whether Ken might be on a Great Western Railway route to Penzance or Pembroke or a local train to a suburb or off to Heathrow to transfer to some destination very far away indeed. Still, it did seem that Kenneth was not planning to go where no man had gone before, but to retrace the routes of his ancestors.

But was it possible? They all wanted to think it was, to verify Min’s theories and to suggest further, probably commercial applications, but also, and most importantly, especially to Nora and Marcus, to be able to believe that Ken was still (if that were the right word for someone in the past or future) alive, that he was someone who might return to them or whom they could follow. The rub was that to test his thesis, now their shared thesis, that time travel was possible and that Kenneth Owens had made a device to allow it, they would have to repeat it. Repeatability is the essence of scientific discovery. Repeating it, if they could achieve it without sharing their--Ken’s--find to the world prematurely, would not be easy.

They decided that it was time to try the food at The Apple Tree Inn. A bit of more relaxed time might let them imagine better how to repeat the conquest that seemed to have been made with Atilla the Hyundai. Besides, when House ordered food, the cost came out of Kenneth’s account. They didn’t know whether, somehow, he might need it to return. So they asked House to call an Uberdu, and Nora called Yanto.

Yanto answered immediately. ‘You’re right,’ he said, without waiting for Nora to speak. ‘Our crazy boy’s a real Time Lord. He’ll probably get a Nobel Prize after all.’

Sunday, October 28, 2018

14. Apples blossom, but they also fall.

27

Owain ordered his men and Kenneth the Strange to stay close together. He didn’t want them to get lost again. None of them knew what dangers might be just beyond a clump of trees or rock. He and Ieuan discussed the situation, and decided that if they followed the river upstream, they might come to the ridge dividing it from the flow of the Sevre, and the could once again make progress towards the sea. So, as they fell into a line of twos and threes, Aidan-who-would-be-Bard fell in beside Kenneth the Strange.

‘Dia duit.’ Aidan broke the silence.

‘Dia is Muire duit,’ replied Kenneth, hoping that he might find out more about where and when they were from this beautiful fair haired lad, whom he had noticed seemed to catch every conversation around him. ‘You look a bit young to be a warrior, if you don’t mind my saying. How did you come to join Owain in his efforts?’

‘So, you’ve heard of Owain Lawgoch? I was hoping to tell his story and make my own name as a bard. Perhaps I am too late.’

‘Not at all. I have heard of Owain, but there are only rumours, and they don’t begin to match. Besides, I try to be something of a chronicler myself, and understand the workings of the world. So, how long have you been following Owain?’

‘Three years. I grew up in Ferns, where it seems every boy is named Aidan. But when I was fifteen, I went off looking for Owain, and caught up with him in the winter of the Gugler War. So far, I must admit, the heroic life has been more full of strife and misfortune than I had expected. Still, strife and misfortune can be an important part in a good story. And you, Stranger, how did you come to our journey?’

‘That’s a long story, but I can try to tell you a short version.’ And one that won’t be entirely unbelievable, thought Kenneth. ‘I was born in London, where my father is a . . . smith, but I spent my summers with my grandparents In Whitby, where my grandmother told me the tales of Taliesin and the other bards. I moved to Sheffield when I was old enough to leave home, and I saved enough to have a tiny cottage near Glastonbury where I could pursue my own studies. I was interested in traveling, so I set forth, not knowing just where I would go. My path crossed yours and here I am.’

‘You must have saved a lot, it seems. Your clothes are like none i’ve ever seen. You wear a torque like no smith’s son I’ve know ever had, but it’s not any metal I know, either. And, if I may be a bit bold, what is that slab of glass you take out and look at when you think no one is looking? Please don’t think I’m prying, but a bard needs to see and know things.’

‘Then you are an excellent bard, I expect. Sheffield is a great place for a smith’s son to learn more about metals and how they work. I found some ways to make knives and other tools that work well and cost less. So, I was well paid. But I spent almost nothing on what most people think of as wealth. I have put everything I have into this trip, so I dressed very carefully. I didn’t know what sort of weather I would find. Since you survived the Gugler War, you know a bit about weather. And this glass slab,’ taking it from his pocket without looking at it, ‘is my most prized possession, although most would find it useless. There are many wonderful secrets to making things of glass.’

As Aidan took the glass, Kenneth’s phone, their hands touched slightly. And Kenneth, not wanting to look at his phone and waken it, looked into Aidan’s eyes instead.

‘Stop’, Owain said quietly but firmly. ‘There’s a village just ahead.’

28

Nearing the village of Castle Cary, the green Great Western train carried two sets of travelers on rather different trips, even though they all had the same reason for the trip. In a First Class coach, Min-seo and Rafael, deep in conversation, were finding their interest in each other deepening with each mile. In Standard Class, deep in silence, Nora and Marcus were pondering what they expected might prove to be their losses. Nora had admired the stubbornness of her only child, but she had often warned him that it would ‘be the death of him’. Now she feared it had been. As the train had left Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s great rail shed, Marcus had averted his worry by thinking about the great advances in travel that had happened in the nearly two centuries since the station had been finished. He was a fan of technological history, especially of the history of transportation, his excuse for keeping an old oil-burning Mazda. And it seemed very possible that his very good friend Kenneth Owens had made something as amazing as Brunel’s shed, as amazing as the original Great Western Railway itself, which was even closer to two hundred years old, even if it had a somewhat discontinuous history. But the his thoughts turned to that discontinuity, and to the deaths that accompanied the early years of the road. And he realized that he still thought of Kenneth as more than his very good friend, and that it was very likely that he would not see him again, and that their relationship would go no further.

Saturday, October 27, 2018

13. What might grow under an apple tree?

25

Two ABB 977’s landed at Gatwick within ten minutes of each other, one in Emirates livery having carried Min-seo Lee from New Delhi, the other sporting BA colours having carried Rafael Acosta from Rio. Both passengers took a ride on the Reading. And so it was that the two scientists found themselves together again, just a week after parting, and with three hours to prepare notes before their next conference. They observed all the appropriate formalities, of course, but they were soon discussing their childhoods and school years rather than antenna theory and manufacturing techniques. Both had been bored, mediocre students in their early years, their brilliance being recognized only when they had begun to study geometry and calculus. Rafael had liked to build things. Min-seo had liked to take things apart. Both had appreciated anime, not just the most famous such as Miyazaki, who had been standard fare of their bedtime videos, or Makoto Shinkai and his blockbusters, but more exploratory and scattered works like those that had come out of Masaali Yuasa’s Science Suru Studio. They had both been intrigued by the description of the future in Mobile Army Riot Police and happy that future, a time in which they now lived, had not happened.

Their conversation wandered to how unlike their lives had been so far to anything that anyone had predicted when they were in school. Although they were barely into their thirties, they had witnessed changes greater than any previous generation, and their own work was contributing to the changes. When Acosta had first begun to be interested in manufacturing, factories were still huge buildings often covering acres under one roof. Now nearly anyone could manufacture anything in one’s garage if the garage were big enough to hold what was being manufactured. When Lee had started work at Kenstel, the big news in antennae really were big antennae. Very large arrays. It had been thought that quantum computers would allow telescopes as large as planets. Now it seemed that one of the most sophisticated antenna yet had indeed been built in a garage in Pilton.

26

Yanto Owens did not share his wife’s tendency to worry. He would say, if pressed, that neither did he share his wife’s tendency to meddle. He thought Nora’s trips to Pilton with Marcus Rutschman were as much about match-making as anything. There were many reasons Kenneth might have missed calling her one Sunday, and he could have simply have turned off all of his connections to the outside world. Maybe he was just on a hike in Snowdonia, or off on some country lane exploring the myths of sleeping heroes with which his grandmother had filled his head. He certainly did not accept her claim that he had gone off on some sort of time-travel. At any rate, he declined the invitation to join her as she went to meet Marcus at Paddington for the train west. He preferred to tinkering in his shop to vacations at Glastonbury, with all its New Age Arthurians.

And so it was that Nora and Marcus met at one of the Paddington Starbucks as they waited to board the Great Western. Marcus was glad for a bit of extra brekkers. He had left Sheffield at the ungodly hour of 5:00 am. He had driven down before, and met Nora at Castle Cary. But his car was a very antique Mazda Miata, not allowed in London with its antique gasoline engine, and since there would be four of them on this trip, he had decided to take the train and rent a car in Somerset. He was grateful at least that there was now a direct East Midland through schedule. For years there had been a long wait in Derby. One of the disadvantages of having been among the first countries to have rail travel was that Britain had a lot of dowager routes and stations that made travel a bit quaint and slow.

Nora was anxious to hear if he had made any progress in understanding just how the bits of gold and quartz he had printed on the roof of Kenneth’s Hyundai might work. Marcus explained that the idea was that they would resonate with a very wide range of wavelengths, and that the analyzing software Kenneth had installed in the car would allow him to determine if any met the criteria he expected for time waves. A big problem being that no one really knew if there were time waves. A bigger problem being that if there were time waves, it was very uncertain that anyone could ‘surf’ them to travel in time. The biggest problem being that all of the evidence suggested that Kenneth might have solved the first two problems and now was off somewhere in time. The so far unspoken problem was whether there were two-way tickets for time travel. They had round-trip tickets to Castle Cary. Kenneth may have found a ticket ride, but Marcus had no way to tell what might be the destination.

Friday, October 26, 2018

12. We're Getting Enough Slices of Apple for a Pie

23

And so it was that Kenneth Owen found himself with the band of followers of an enemy of the kings of 14th century France and England, Owain Lawgoch, traipsing through what Owain thought to be Poitou as he tried to find the River Sevre. As they clambered down the slope towards what they thought would surely be the stream, Iauen Wyn suggested that they must have wandered much farther in the storm the night before than they had realized. The ground was too hard and stoney, the slopes too steep, for Poitou. Nothing looked right. And yet the landscape looked vaguely familiar, but not right, not real, not quite any place anyone could remember.

After about an hour and a half, they came to the river. It, too, was wrong. Terribly wrong. It was not a placid stream rolling through farm lands, something they should by now have realized they were not in as they wandered down rocky hills, but a feisty mountain river. And, it ran the wrong way, not leading them northwest towards the coast they sought but southwest towards who knew where. Still, it was a very cloudy day, the sun not really visible. Perhaps, Iauen suggested hopefully, they were just disoriented, that they hadn’t know the countryside as well as they had thought, that a clearer view of the sky might help them orient themselves.

24

Kenneth Owens’ tiny cottage barely had room for the four detectives to sit around the Table, although it kept them well-supplied with food and drink on demand. Sleeping had to happen elsewhere. There were of course plenty of inns nearby, so Marcus and Rafael and MIn-seo took rooms for the weekend at The Apple Tree, in Glastonbury. It was as different from Kenneth’s modern prefab cottage as anything could be,having been there forever, under a variety of names. It was pricier than some, but it was close to the Tor where Kenneth had last seemed to be. It had been Rafael Acosta’s idea. He did not mention that he thought it would be romantic when he suggested it, only that he thought was in a convenient location and that he liked the allusion to Avalon.

Of course, Kenneth had a phone with a magnetometer in his pocket, a bit of tech that didn’t need wireless connectivity, and he slipped it out, furtively. Indeed the river they had found ran southwest. He quickly repocketed his modern magic, thinking no one had seen him. But Aidan Prydudd had seen. Indeed, Aidan had been watching Kenneth carefully all the while. He was quite intrigued by this stranger, who seemed strange in more ways than usual. And intriguing in more ways than usual.

Thursday, October 25, 2018

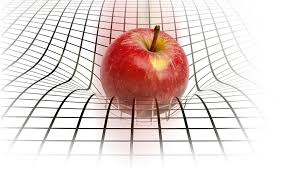

11. Another healthy Serving of Einstein's Apple

Ken was both excited and worried by Owain’s proposal to travel together. Owain was one of the legendary sleepers of Celtic mythology that his grandmother had told him about. His was one of the legends that had made him think of the possibility of slipping into another time, long before he had thought he might be able to do it himself. It was a perfect opportunity to see if there was anything to his ideas. But he was also worried to leave Atilla behind. It was fairly out of sight, amidst a brushy thicket, but it could easily be found by some rabbit or deer hunter. What they might make of such a device he had no idea. Would they burn it as witchcraft? And even though he could find it again with it homing signal and it could come to him if he were within line-of-sight with it, hills and valleys would block any attempt he might make to activate it, and he doubted if they were anywhere/anytime covered by Google Maps.

Nevertheless, he accepted Owain’s invitation. ‘Where are you headed?’

‘Northwest to the coast, to go back to Britain to claim what is mine.’

Owain’s response found Kenneth completely off guard. He had assumed that he was near Glastonbury, perhaps in Kings Castle Woods, or maybe around Gypsy Lane, where there were a lot of thickens like the one where Atilla had lodged. He had thought Owen might be bound for Abergwyngregyn or London. He had not thought that they might be east of the Channel. But, he realized, he really had very little idea of where or even when they were. Indeed he might be in a dangerous time for a Welshman. What better Welshman with whom to face danger than the Red Hand?

22

Min-seo was excited by Marcus’ suggestion that her theories had, or might have, worked. She asked him to send her the files that had to do with the fabrication. And, although she realized that they could easily have worked together online, she suggested that they meet in person, and that they invite Rafael Acosta as well. The only question, beyond when, was where. It did not seem a good idea for the press to have Kenneth’s potential time travel story to sensationalize. Besides, Min realized, there might be intellectual property rights issues she had not begun to think about when she had assumed Kenneth’s work was just theoretical. So it was agreed that they would meet in Glastonbury for a ‘tourist weekend’ the following Friday, and that they would invite Rafael Acosta to join them.

Not surprisingly Acosta was happy for the invitation.

An Apology for my Life: I Ain't out to Save the World

This little essay is a response to a comment a friend of mine made on Facebook, in which she said, 'Dale, who stirred it up down the commentary line, is well into his 70's and has the smallest carbon footprint of anyone I know. He is a constant reminder to me that these are small steps towards a bigger change in lifestyle, one that the millennial generation is experiencing.'

The commentary line had been about saving the world by not using Big Oil, about bicycling or walking as an alternative to driving cars, because cars are supposed to be causing global warming and the end of the world as we know it, and Big Oil leads to beheadings in the Middle East. I had pointed out that beheadings are an integral part of the culture and religion of the Middle East long before British Petroleum (See, for example, the Book of Judith), and that I didn't expect the world would end because of us, now matter how much hubris we had, but that cars would soon no longer need us and they might kill us off as unnecessary clutter.

What I want to make very clear is that I don't walk or ride a bicycle or live in a very small house because I want to save the world. I do those things because I enjoy having few chores and because I like to experience the world. I have just about finished the construction of a tiny house--I still want to paint the now-white front door red--and I no longer have a kitchen. Cooking means one has more dishes to wash and general splatter to clean up.

I am well into my seventies, and the changes in my lifestyle since I had a Chrysler mini-van and a Jeep Wagoneer and a golden retriever and a big tudor house where I hosted sit down dinner parties for thirty-two people have mostly been in small steps, and with each step I have found I enjoyed life more. I have never read Tom Robbins, but I find that the statement attributed to him, 'Life is too precious to waste on a career', applies to a lot of things besides careers. It's too precious to waste on car payments and spending hours each day in traffic jams, it's too precious to waste on mortgage payments, or on seeking the kind of approval that is most often the real goal of giving large parties. (Although I did for many years give very simple parties, just soup and bread and coffee, because I like to see what happens when groups of assorted people converse. Now I can see that happening on Twitter, without having to wash all those soup bowls.)

I'm not even convinced that the activities of us folk is the major cause of global warming, which has been going on since the last ice age. Certainly the world is getting warmer, but the global climate is a very complex system. One of the major motives for developing modern computers was an effort, starring John von Neumann, to make accurate weather predictions for the allied forces in World War II. The effort pretty much failed, at least in von Neumann's lifetime. I know, of course, that the majority of the world's climatologists agree that humans are the cause, but humans are a species prone to hubris, and the majority of the physicists a century ago thought Einstein was wrong. I have found Freeman Dyson's suspicions about our abilities to understand the complexities of climate more convincing than the folks who want to monetize our fears. I am well into my seventies, and I remember when the world was being destroyed by acid rain and when it was being destroyed by over population.

But if I did think that driving and other human activities were destroying the future viability of human life on this planet, and that human life on this planet was worth preserving, I would park my car and turn off my air-conditioner and watch Altered Carbon on my phone instead of my big-screen LG. And I would not blame Big Oil for catering to my addictions. (I have found fewer more clashing ironies than the bumper stickers that flourished after the grounding of the Exxon Valdez saying 'Boycott Exxon', as if gasoline could be delivered by fairy moon dust and that ships had not had a very long history of wrecking.

Of course, heroic saviours have long been popular in the stories we tell ourselves, whether Jesus in a religion , or Arthur in romances, or Lucy in the Wardrobe, or Link in Hyrule or Neo in the Matrix. Joseph Campbell became rich and famous describing the Hero's Journey. I think it is probably important that we be the heroes/heroines/ of our own journeys. But when we think we are the heroes of every journey, that we are saving the world, well, I think I will skip the examples like Boney or American politics and just remember wise Puck in Midsummer's Night Dream. What fools we mortals be.

Wednesday, October 24, 2018

Slice the tenth

19

Owain had wakened with his men, feeling dazed and confused, and not a little hungover, although he had not drunk anything stronger than water on the last day he remembered. Looking around in the mist, he saw only his loyal Cymraeg companions. None of the Aragonese mercenaries were to be seen. But there was another man emerging from the mists, a stranger. Owain studied him carefully.

The stranger was dressed much as a peasant, but he was wearing very new and expensive-looking clothes. His neck was circled by a strange torque that also looked expensive but made of something besides normal metals. His hair was closely cropped. Perhaps he was on pilgrimage, perhaps as a penance.

‘Dia duit,’ said Owain to Kenneth. ‘Dia is Muire duit,’ responded Kenneth. The two men stood regarding one another warily. Neither one knew how confused the other was, nor did either one want to reveal too much. Owain felt as if he had slept for years, or at least he had dreamed of years passing, and Kenneth knew only that he was in some other time than he had left. He thought he should avoid the alien cliche of ‘take me to your leader’, but he wasn’t quite sure how to elicit the information he wanted so badly.

Again, Owain broke the silence between them. ‘A fine day for travel, it seems. Have you far to go?’

‘I am a Glastonbury pilgrim’, said Kenneth, consciously choosing not to say if he were a pilgrim from or to Glastonbury.

Owain recognized none of he more common pilgrim badges. The stranger might be on his way to Santiago, but he wore no scallop shell. Perhaps the medallion hanging on his chest might contain a relic or image of some saint. ‘So, is it to Campostella that you are headed?’

‘Not really. I have saved for a long time to be able to wander just to go where I might go and to see what I might see. This morning my trip has brought me to you. I am Kenneth ap Yanto ap Owain’

‘And I am Owain ap Thomas ap Rhodri. These are dangerous times to be a Welshman. Perhaps we should travel together.’

20

When Marcus opened his files of recent correspondence with Kenneth on the Table, it woke to reveal many other open tabs. Kenneth had chosen not to close those files before he left. If he got back soon, or if he failed to leave, there would be no need to have them hidden. And if he didn’t get back, soon or ever, he was sure that at least his mother and perhaps Marcus would come to investigate. There was no need to hide his project when it would be too late for them to try to dissuade him, and he didn’t want anyone to think there had been any foul play. It didn’t take long for Marcus to surmise what the project was.

Min-seo Lee had just started eating a bit of dinner in her kitchen in Chandigargh when she was surprised by a Duo call from Marcus Rutschman. She had been at the Kenstal labs in Kunli most of the day, talking with production production engineers about possible ways to manufacture her next concept micro-antennae. She was sure her theories about resonance were correct, but putting them into materials presented a lot of problems, and the Kenstal engineers weren’t sure they could be overcome. She was happy, she admitted to herself, to have an excuse to get back in touch with Rafael from the Connectivity Conference. His company specialized in manufacturing solutions.

Marcus Rutschman was well enough known that she accepted his call, even though she would usually have just let a bot reply for her, offering to save any message for later. Besides, she was familiar with his work in nano-printing, and she had taken several of his pubs with her to show to the engineers in Kunli.

‘Please forgive me calling with no notice, Miss Lee, but I have a sort of potentially emergency mystery here in England, and you may have the clues I need to solve it.’

‘Please forgive me if I eat while we talk. I have had a long day at the lab, and oddly enough, your work came up then, so this may be a helpful call for both of us. What’s your mystery?’

I am at Kenneth Owen’s house. The woman here with me is his mother. Kenneth seems to have disappeared. He had no presence, physical or virtual, since last Halloween at about midnight. He left a lot of files open here, and a lot of them involve you and your work on resonance to allow small antennae detect very large waves.’

‘Ah. Yes. We had many conversations about that project of his. I shared my theoretical data, but I have not been able to make the antennae. I never quite understood what particular sorts of waves he was trying to detect.’

‘I think I made the antennae for him. And it seems he was looking for time waves. He thought he could travel on them.’

Tuesday, October 23, 2018

Nine. Maybe not enough apple for a pie, but at least enough for a turnover.

17

When Ken had dressed, he had thought about the possibility of arriving in any sort of weather, but he had also thought about the possibility of arriving in any sort of culture. He was dressed in brown, with laceless boots, slightly baggy, zipperless pants, and an anorak that would pass for a tunic from just about any era. He was not at all sure how people he might meet in another time, if indeed he did meet people in another time, would react to his dropping in, so he wanted to seem as little like an alien as possible. Communication might be a more difficult problem. His Google Galileos would translate any known language for him, but if he also used them to speak it might seem very strange for the sound to be coming from behind his ears, with the default speakers, or from a medallion hanging like a necklace, connected with wifi, as he considered using. He had decided that the best option was probably a neck piece, rather like a torque. Then the sound would come from near his mouth, and he hoped he could hope to lip sync well enough not to rouse too much suspicion. He had purposely let his moustache grow rather long, to cover much of his mouth, so lip readers would be frustrated. He hoped he would not arrive at a time when facial hair was alien.

Now he just felt silly. All his work and preparation and forethought wasted because of lightning’s striking the Hyundai and his dozing off to sleep. Rather than being in some other time, he was in the dregs of someone’s Halloween party. Two of the ‘knights’ walked towards him. One of them spoke. He spoke in Middle Welsh, in Cymraeg Canol, the language of The Mabinogion.

II

18

Kenneth’s little cottage spoke several languages. Wednesday afternoon, it recognized Nora and Marcus, welcomed them in English, and invited them in. Still not having heard from Kenneth by Tuesday, nor even from his telephone, Nora had remembered that the house had a number as well, and had called it. She wasn’t quite accustomed to the internet of things, but was happy to hear that Kenneth had left for Glastonbury late Halloween. It was a clue, at least, to her son’s whereabouts. She had taken the Teslatube over and met Marcus on Wednesday morning at the Tor. Marcus had gone over the details of Kenneth’s printing project, and had begun to suspect what might be involved in the ‘field trip’. As he had expected, there was no evidence of Kenneth nor the Hyundai at Glastonbury. So, they had gone to Kenneth’s cottage to see if they could find more clues.

The two guests accepted the host house’s offer of coffee and biscuits and sat at the table. The more they looked around, the stranger everything seemed. Indeed the car was gone. But Ken’s I.D. and money cards were on the counter. There was no sign of any sort of break-in or violence. Everything was spotlessly neat. Of course the house kept everything spotlessly neat, but it would also have sent a distress signal if anything unwanted had happened.

It was now two days after Halloween, and Kenneth had suggested to Marcus that that might be the date of some field work, so he laid his Google Plexus on the table to share the most recent correspondence he had had from Ken with Nora.

II

18

Kenneth’s little cottage spoke several languages. Wednesday afternoon, it recognized Nora and Marcus, welcomed them in English, and invited them in. Still not having heard from Kenneth by Tuesday, nor even from his telephone, Nora had remembered that the house had a number as well, and had called it. She wasn’t quite accustomed to the internet of things, but was happy to hear that Kenneth had left for Glastonbury late Halloween. It was a clue, at least, to her son’s whereabouts. She had taken the Teslatube over and met Marcus on Wednesday morning at the Tor. Marcus had gone over the details of Kenneth’s printing project, and had begun to suspect what might be involved in the ‘field trip’. As he had expected, there was no evidence of Kenneth nor the Hyundai at Glastonbury. So, they had gone to Kenneth’s cottage to see if they could find more clues.

The two guests accepted the host house’s offer of coffee and biscuits and sat at the table. The more they looked around, the stranger everything seemed. Indeed the car was gone. But Ken’s I.D. and money cards were on the counter. There was no sign of any sort of break-in or violence. Everything was spotlessly neat. Of course the house kept everything spotlessly neat, but it would also have sent a distress signal if anything unwanted had happened.

It was now five days after Halloween, and Kenneth had suggested to Marcus that that might be the date of some field work, so he laid his Google Plexus on the table to share the most recent correspondence he had had from Ken with Nora.

Monday, October 22, 2018

Eighth portion

15

Nora Davidson Owens was worried. Her son had not answered her call. That was not unusual. But there was no ‘your son regrets not to answer your call now, but he will return it soon’ message. Instead she heard ‘The BT customer you are attempting to call is offline. Please leave a message, and it will be forwarded as soon as possible.’ That had been last night, and it was still the only response she received this morning. Ken was never offline. Something was wrong. A mother knew these things.

The father meanwhile, was not worried at all. Yanto Owens was, it is true, always a bit disappointed in his son, whom he was sure should do something to earn a Nobel Prize, or at least a Turing Award. But he had accepted that Kenneth would always explore his own path, and he had even become a bit proud of his son’s stubbornness. Ken was always up to something. Maybe one of his experiments, which Yanto never quite understood, needed him to be ‘offline’ so he could take some more ‘readings’. To Yanto, a metallurgist who liked to work with and theorize with nice ‘solid’ objects, even if sometimes they were molten or even vaporized, Ken’s readings may as well have been of Tarot Cards. His oft-repeated admonition to his son was ‘Be whatever you want to be, but be the best.’ Ken had seemingly been a much better astrophysicist than Yanto a metallurgist, and in that he took pride, but leaving even a third-rate university for a cottage in a tourist trap of a town seemed an unlikely career move. It was a long way from Pilton to Paris or Bern, even on the internet. Or so it seemed to Yanto Owens.

Nora, truth be told, was more disappointed in her son than was Yanto, although she would never have admitted it. She wanted family. She had wanted more children, but could never convince her husband that the time was right for another little Owens, so all her eggs were in Ken’s basket. She had adjusted to his being gay: lots of gay couples adopted children, and Ken’s stubbornness came with a patience that she had been certain would make him a great parent. When she had met Marcus, she was ready to order a cake. He seemed everything a mother would wish in a son-in-law: handsome, witty, well-connected, very smitten with Ken, and with beautiful brown eyes. But they had never become so attached as she had hoped. Marc had continued to visit her and Yanto in London even after Ken had moved to Pilton,and Nora had thought the subtext of his visits had been how to get Ken back, but nothing like that had ever been said, and Ken had seemed just as happy living a solitary life as he had when he and Marc were ‘seeing each other’.

Kenneth seldom came to London, but he did chat with his mother nearly every Sunday. So, when he had not called this time, she thought he must be up to something important. She was patient. Had not Ken inherited his patience from her, just as he had inherited his stubbornness from Yanto? But on Monday, Halloween, her patience thinned. She had thought he might like to come up to London for All Saints. She thought that if he did, she would invite Marcus, who might want a bit of lead time. But there was nothing she could do. There was Instagrams, and that seemed possible for an invitation to an impromptu dinner party. Tuesday morning, she tried to call again. Tuesday noon, she tried to call again, Tuesday evening, she tried to call again. Tuesday night, she took motherly action, and called Marcus Rutschman.

16

It would be false to say that Kenneth Owens had been the last thing on Marcus Rutschman’s mind when Nora called. Ken always hovered around the edges of his thoughts, but he doubted that Ken thought often of him. Nora, yes. Ken, no. Ken seemed to be on a path without companions, It had come as no surprise that when he bought a car, a very high-tech car, it had been a single-seater. Certainly Ken in the flesh could be full of passion and attention. No one Marc knew was a better lover. But Ken’s true love was his work, for which the university post seemed just a cover, and which remained something of a secret. The passion and attention he gave to his work was even greater than he gave to Marc. When Ken had moved to Pilton, Marc knew that if was for the work, whatever that was. When asked about it, Ken would simply say that it might be dangerous to share it. Marc almost felt that Ken could be a spy.

His own work, however, was very public. As head of research for the Sir Henry Royce Institute, what he did was highly publicized. The Royce Institute had grown from a centre for reinvigorating British manufacturing to a partner with countries around the world. He helped develop production systems, so that Sheffield’s exports became much more than physical products. Many of their students and many of their customers were not only from the usual suspects, China, India, and Brazil but from Greenland and Australia, Argentina and the Philippines. Ironically, his work with materials gave Marcus a rich field for discussion with Yanto Owens, who tried to keep up with what was happening his metallurgy even though his own projects now were seldom bigger than making false relics for celtic re-enactments.

Ken had also taken a keen interest in Marc’s work when he wanted to print a strange weave of metals and semiconductors onto the surface of his Hyundai. No one knew more about 3-D printing than Marcus Rutschman, so he had happily helped Ken get Atilla ready for what Ken had called ‘possible field work’.

Marc immediately saw how worried Nora Owens looked on his watch. She had hoped, she said, to invite a few people for a holiday meal, and had hoped Marcus could come, but she had a problem. Ken had disappeared. She told of trying to call him, with no response, that there had been no distress signals from his house or his car or his phone, but that neither his phone, glasses, or car were online anywhere. Only the house responded to her inquiries. “Mr. Owens left Monday night, ma’am, and didn’t say when he would return’ was all she knew. It was unlike Ken to be offline. He had not called Sunday. Did Marcus know anything?

No. He didn’t. He hadn’t heard from Ken for a fortnight, and then Marc had called him to see if the printed project were working allright. Ken had said that everything seemed to be fine, and that he would know for sure around Halloween. Probably he was doing the ‘fieldwork’ he had mentioned when he modified the Hyundai. He had enough electronic magic in that little car to become ‘invisible’ at least in most ways, if he wished. No need to worry. Still, Marc assured Mrs. Owens, he would check around, and let her know if he found anything. Ken might be working with someone at the University. He’d let her know what he found.

Sunday, October 21, 2018

The Seventh Slice

13

Ken felt as if he were waking, but he couldn’t quite open his eyes. He felt as if he were still dreaming. He was sure he had actually come to the Glastonbury Abbey parking lot, and that it had started to rain, and that he had seen on his screen a suspicious wave signature at around 100 hertz. He had told Atilla to go towards the Tor, but then it seemed he had dozed off. Surely he was not sleeping. What if the whole night were a dream, what if he had gone to sleep despite his anxiety that this was the time his years of work and speculation had hopefully come to fruition?

He opened his eyes. He was in the Hyundai, but not in Somerset, unless he were in King’s Castle Wood. Nonsense. He was certain he had told his car to go to Glastonbury, that it had, that it had started to rain. He remembered the trip. Of that he felt sure. But what if he had dozed off, and somehow the Hyundai had driven itself to Wells instead of towards the Tor. He didn’t feel certain, really, of much of anything, except that it seemed no longer to be raining and that he really wanted to wake up. It was still night when he opened his eyes, a moonlighted night, with the trees around him and their shadows seeming to dance a taunt. He glanced at the gps display: ‘no signal found’. Had the clouds brought not just a bit of rain but lightning? Had his car been struck? He scrolled down his Galileos. ‘No signal found.’ ‘Open door’, he told Atilla. It did. At least something still worked. He looked around to find himself in a Halloween party. He found himself surrounded by grown men in very realistic medieval soldier costumes.

14

Ieuan Wyn found himself waking. He had had such a strange dream. He, the one the French called le Poursuivant d'Amour, Continuing Love, and a few faithful others, had followed Owain, against their better intuitions, into a huge storm, pursuing the English betrayers. It had seemed very real but very unnatural, and now he wondered if they had been bewitched. There were stories around that the new King, Richard, would hire witches and wizards to carry out the tasks his grandfather’s assassins had failed to accomplish. Maybe they were true. If it were true, if he and his companions were bewitched, none of them would be in any position to help Owain now. Hopefully some of the men who had been more awed by the storm would mount a rescue. Or he might just wake to find that after the dream they were all still in Poitou with the English in control of the Mountain.

Ieuan looked around. They were in some sort of cave, thirteen men in all, counting young Aidan who was just coming in with his breeches half-belted. He was not surprised that Aidan had followed Owain into the cloud. He might not be expected to do much in a fight, but that would not because he lacked bravery. He was convinced that he could do more with his poetry to deliver Cymru from the English than had been accomplished with swords. So far, he had done as much.

Saturday, October 20, 2018

Sixth Slice

11

It began to rain in Aidan’s dream. The rain seemed very realistic, so realistic he felt he should go out of the cave to take a piss.

12

Min and Raf left the Odeon to find a gentle mist had replaced the rain. They decided to walk the 15 blocks or so back to the Gresham. There were still many ghouls and spirits about, and in the mist they seemed quite proper. It was easy to think that this night might really be a thin time, and that some of the visions in the mist were not in costumes at all, but inhabitants of some other world who were celebrating the night with the young engineers.

Min and Raf, however, paid them little attention. The night had become a serious date, but neither quite wanted to admit it. If their feelings were not mutual, there would only be disappointment. So they talked about other conferences and gatherings coming up, when they might meet again, ‘to talk about their theories’.

Too quickly they were back in the lobby of Min’s hotel. She did not invite him up, of course. He bowed, knight-like, and kissed her hand, holding it a little longer than necessary, and returned to the night.

Friday, October 19, 2018

The Fifth Slice

9

In Dublin, too, it had begun to rain. Rafael suggested the fireworks at midnight might be a soggy affair. Perhaps instead they might find something to do indoors. It could be fun to see Rocky Horror Picture Show. It was playing at the Odeon, and they were almost there. They were both virgins. It seemed a good idea to Min, who hadn’t put on her best hangnok to get it soaked. And so, two brilliant and reserved scientists found themselves surrounded by a crowd of enthusiasts with lighters and newspapers, water pistols and noise makers, wearing fishnet hose and throwing rice and confetti and toilet paper at each other. They danced the timewarp, again.

10

There were parts of Ken’s theory that he himself didn’t understand. It was not even a theory that he could quite explain, and he wasn’t sure whether his experiment tonight would disprove it if he remained in the same time and place. He was not even sure that there was any advantage to his coming to Glastonbury to try it. Glastonbury did have a reputation for being a ‘thin space’ going back more than 2,000 years, a place where people traveled between the worlds. If Ken were right about being able to ‘surf’ on gravity waves, then this place was the Mavericks of timespace surfing. Maybe.

Most accepted laws of physics suggested that time is reversible. But that seemingly possible phenomenon had never been observed, or so it seemed. But if the reversal of time happened not in this universe but in a parallel one, one separated from us by a very small distance, it might be real but unobservable. Roger Penrose had thought such a thing might be possible, and might account for dark matter. Indeed, Ken thought, it had been encompassed by Newton’s third law. If one thought of gravity waves as breaking, as do waves of water on a beach, there would also be an undertow. Ken thought such a similarity was probably accurate, and that just as many other waves, when they collapse,

become observable as particles, gravity waves collapsed as observable ‘particles’ of time. Ken found it fascinated by how clearly some of the problems of understanding such things had been expressed as long ago as 1915 by Bateman in his Mathematical Analysis of Electrical and Optical Wave-Motion, as he wondered what ‘medium’ light and electricity moved through: ‘If we abandon the idea of a continuous medium in the usual sense, only two ways of explaining action at a distance readily suggest themselves. We may either think of the aether as a collection of tubes and filaments attached to the particles of matter as in the form of Faraday’s theory . . . ; or we may suppose that some particle or entity which belonged to an active body at time t belongs to the body acted upon at a later time t+T. . . .if particles are continually emitted from an active body they will form a kind of thread attached to it. . . . At present we are unable to form a satisfactory picture of the processes . . . .’ (Cambridge, 1915, pp. 4-5) Ken hoped that there were some sort of thread attached to ‘an active body’ because he hoped to be one of those active bodies, and he hoped, like Theseus in the Labyrinth, to follow the thread back home.

Thursday, October 18, 2018

Einstein's Apple, Slice Four

7

Ken had liked the idea of the Hyundai Harmony when he first heard of it. It was harmony that had been among the first discoveries about waves, made by the Pythagoreans or their teachers. It was also the first affordable car made of BoeingBus’s carbon-fibre/microlattice materials. It was strong and light and stiff, and able to absorb shock. Since he didn’t know exactly what he was getting into, Ken thought he would need all the help he could get. It was a very small but very smart car, with all the navigational and information capabilities one could hope for in 2039, responding to voice or gesture, and piloting itself. It was also very adaptable. He had removed the jump seat, leaving only one, so he would have room for extra batteries and water generators and air purifiers. He didn’t expect to need them, but he would have them if he did. And then there was his special take on Min-sao Lee’s antennae array that he hoped would turn his Atilla the Hyundai into a surfboard. Because he knew, he thought, what he was looking for, his antennae were not very large, but they were printed directly onto the upper surfaces of the Hyundai. Not only was living in a tiny pre-fab in Pilton cheaper than living in an ‘historic’ cottage, it also provided for much better atmospheric control for nano-printing, which he had been able to afford because of his savings in rent. The Hyundai came with what should be plenty of on-board computing power for his tuner, which was a damper, actually. He had added another, parallel NVIDIA Gamma one, and a 10 terabyte SSD on which he had stored profiles of his expected waves. Because the waves he was looking for were extremely long with relatively low amplitude, they were easily drowned out by the noise around them. So he used the data gathered by calibrating the usual background noise to make dampers that would show only the variations in noise that gravity waves would cause, and in real time so he could ‘see’ his wave rather than analyze it from the data later.

He was sitting in this parking lot at Glastonbury Abbey on Halloween because he, like Min-sao Lee, had spent summers with his grandparents. His grandparents, especially his mother’s mother, had filled him with celtic folk tales. Before Ken was born, Blanche and Aubrey Davidson had retired to Whitby, a town Blanche considered the site of betrayal for the celtic tradition. The basketball team might be saints, but she was certain the term was misused for Hilda. As a child, he had found his grandmother’s stories amusing, and her clinging to them quaint. But as he grew, he wondered what might be the physics behind some of the phenomena she described. There were so many heroes who disappeared, who were said to be not dead but asleep, who would return. Aubrey had given him his first appreciation for waves when he took Ken out in his sailing dinghy. There was no end to the variety of waves, nor of what they could teach. They not only were the condition for sailing, they could tell what conditions to expect. Their interactions could be spectacular, and it was from clapotis that Ken began to learn how waves might be modulated and even made to stand still. The air, too, operates in waves, and they could be read in the clouds above but also on the surface of the water.

Now the parking lot around Atilla the Hyundai was beginning to be a surface of water. Would, Ken wondered, the rain be a variable he had not considered?

8

Owain Lawgoch, Owen the Red Hand, was not the only one who dreamed he was waking that Samhain evening. He was surrounded by twelve of his warrior companions. He would have been happy to know that legend had made him a greater leader than he could honestly claim to be, with a band of forty to hundreds of warriors. But few had been brave or foolish enough to follow him into the storm in which they fell asleep.

One of them was Aidan Prydudd, hardly more than a boy, not really a warrior at all but, as his name suggested, a bard, and a romantic bard at that. He had accompanied Owain into France to be able to sing of his glories and to gain a valuable patronage. But the English had found out their plan, and now they were assumed dead. Indeed, Aidan sometimes wondered in his dreams, might they be dead? How could one know whether one were dead or but asleep. Sometimes it seemed he might be waking, but always someone would say ‘sleep on’ and he would, perchance to dream. Sometimes he dreamed himself not a bard but a fool. Perhaps he was misnamed. Perhaps he should be called Aidan Ffwl.

Wednesday, October 17, 2018

The Third Slice

5

The Hyundai had parked in the lot at the Glastonbury Abbey at 20:40 GMT. A warm rain had begun to fall. Ken had plenty of time to go over his checklist again, not that he really needed any more preparation.

Ken had retired early from LIGO/NANO a year ago. For twelve years he had worked at the University of Sheffield, but he had moved to a little cottage (a new cottage, true, but small) in Pilton when he had convinced the University and LIGO/NANO that he could work as well at home as in the lab, not a difficult task in the time of high-speed optical cables. He had wanted to be close to Glastonbury. For three more years he had stayed on, but now he had no official duties. His parents and many of his friends had tried to convince him to continue in what they called his career. His parents, who lived in London, had repeatedly told him that he was wasted at Sheffield, that he would be welcome at Cambridge or someplace in the United States. His mother had hoped for Cambridge, where she could see him more often. His father had hoped for the University of Washington, where there was more money. But Ken liked where he was, in the backwater of Sheffield. He had access to any work anyone was doing with gravity waves anywhere, but his required contributions were low. He had enough money and enough time to pursue what interested him most.

There had been other protests about his move to Pilton, and not even into some historic weaver’s cottage but into a new prefab unit that could have been anywhere. His father thought it was not suitable for a young man about whom everyone had had such great expectations. (Is one still a young man at 37? There wouldn’t be much more time for him to do the Great Work that would result in a Nobel Prize.) His mother was more concerned that he was leaving behind the person she had chosen as the great love in her son’s life, Marcus Rutschman. Marc did nanotech research, exploring biological based semiconductors. Everyone said he was a genius. Nora Davidson liked his eyes, and how polite he was. Although it seemed to her that Ken and Marc were an obvious pair, Ken had never seemed to be as interested in a mate as she. She never quite understood what it was that interested him.

What interested him were waves. LIGO had ‘discovered’ gravity waves in 2016, but there were still many things about them that were understood only theoretically. Now, if we live in spacetime, as we clumsily have said more or less since Schopenhauer, and maybe since the Incas, then the wave is a perfect analogy, Ken thought: it has a spatial extension, its amplitude, and a time extension, its frequency.

Human beings had long developed sensors to detect many kinds of waves. Our skin picked up heat. Our inner ears detected seismic waves. Our eyes detected a range of light waves. Our ear drums resonated with sound waves. And we had learned to detect many kinds of waves with post-meatware evolution. Thermometers and microphones and seismic sensors and microphones and photography all extended the range of waves far beyond those known to us with our biological senses. Radio antennae of many kinds allowed us to use a broad range of frequencies. Sometimes we would discover a wave with our new extra-biological senses, as Roentgen and Curie did with photographic plates. Sometimes our theories of physics would lead us to look for ways to detect waves. It was the theory of gravity waves that had led to the development of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory and the LIGO Scientific Collaboration of which Ken’s work at Sheffield was a part.